Rinzai Zen (臨済宗, Rinzai-shū) stands as one of the prominent schools of Zen Buddhism, tracing its origins back to the Linji school of Chan Buddhism in Tang Dynasty China.1 Known for its direct and often intense approach, Rinzai Zen emphasizes the pivotal experience of kenshō (見性), often translated as “seeing one’s true nature,” as the initial gateway to authentic Buddhist practice.2 This initial insight, however, is not the culmination of practice but rather the starting point for a rigorous and prolonged period of post-kensho training aimed at deepening and fully integrating this awakening into the fabric of daily life [User Query].

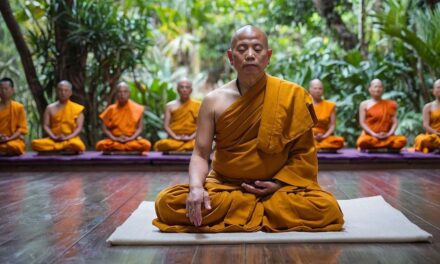

Characterized by intensive seated meditation (zazen), the strategic use of paradoxical riddles or stories known as kōan for introspection, and a central relationship between student and Zen teacher involving private interviews called sanzen, Rinzai Zen distinguishes itself through its dynamic methods and historical connections to the samurai class of Japan [User Query]. While shikantaza (“just sitting”) is a recognized practice, it holds less emphasis compared to the Sōtō school of Zen [User Query]. Today, Rinzai Zen in Japan exists not as a singular entity but as a collection of 15 distinct branches, each with its own head temple, with the Myōshin-ji branch standing as the largest and most influential [User Query]. Its historical depth and unique characteristics have cemented Rinzai Zen as a significant force in both Eastern and Western spiritual traditions.1

The Genesis in China: Linji Yixuan and the Foundations of Rinzai

The emergence of Rinzai Zen is intrinsically linked to the flourishing of Chan Buddhism during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) in China, a period marked by significant cultural and religious exchange.6 Within this vibrant landscape, Linji Yixuan (臨済義玄, Rinzai Gigen) (d. 866 CE) rose as a transformative figure.6 Born into the Xing family in Caozhou (modern Heze in Shandong), Linji embarked on his Buddhist journey at a young age, traveling extensively to study various Buddhist teachings.6

His path eventually led him to the tutelage of Huangbo Xiyun (黃檗希運), under whom he initially struggled to grasp the fundamental principles of Buddhism.9 According to the Record of Linji, Linji’s persistent questioning of Huangbo about the core meaning of Buddhism resulted in repeated strikes with a staff, leaving him in a state of confusion.6 On the advice of the head monk Muzhou, Linji sought guidance from the reclusive monk Dàyú (大愚), whose seemingly simple response triggered a profound awakening, a realization of the emptiness of conceptual thought and the inherent truth within oneself.6

Following his enlightenment, Linji returned to Huangbo, his understanding now clear.9 Inspired by his master’s teachings yet forging his own distinct path, Linji’s approach to Chan Buddhism was characterized by directness and an often confrontational style aimed at shattering the conceptual prisons of his students.9 His methods included sudden shouts (katsu) intended to startle students out of their habitual thought patterns, and physical blows administered with a fly-whisk, a symbol of a Zen master’s authority.9

Linji’s teachings, preserved in the Recorded Sayings of Linji (Línjì yǔlù 臨濟語錄; Japanese: Rinzai-goroku), emphasized the inherent Buddha-Mind present in everyone, advocating for a deep faith in one’s own natural, spontaneous mind.6 He famously espoused an iconoclastic attitude, urging students to transcend dependence on external authorities, even stating, “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him!”.9

This radical assertion was not a literal call to violence but a forceful encouragement to break free from all forms of attachment and to discover their own Buddha-nature.12 Linji also stressed the importance of non-dependency, encouraging individuals to rely on their own inner wisdom, and introduced the concept of the “True Man Without Rank,” the pure, unchanging essence within each being that is the source of all understanding.6 Furthermore, he taught the significance of living fully in the present moment, urging his disciples to simply be their ordinary selves in ordinary life, without striving for some external notion of Buddhahood.9

While Linji’s life and teachings laid the groundwork, the formal establishment and widespread influence of the Linji school as a distinct entity within Chan Buddhism primarily occurred after his death during the Song Dynasty (960-1279).6 Figures like Shoushan Shengnian (首山省念), a fourth-generation descendant of Linji, played a crucial role in solidifying the school’s foundations and promoting its teachings.6 It is also important to note that the Linji lu itself, the primary source of our understanding of Linji’s teachings, is not a verbatim transcript but rather a compilation that evolved over time, reflecting the developing identity and aspirations of the Linji school.6

The Core of Rinzai: Emphasis on Kensho

Defining Kensho: Seeing One’s True Nature

At the heart of Rinzai Zen lies the profound emphasis on kenshō (見性), a Japanese term derived from the Chinese jianxing, which literally means “seeing nature”.21 In the context of Zen Buddhism, kenshō refers to an initial, direct insight or awakening into one’s own true nature, often equated with Buddha-nature, ultimate reality, or the Dharmadhatu.21 It is a moment of seeing clearly into the fundamental nature of existence, a glimpse of the non-dual reality that transcends ordinary conceptual understanding.21 It is crucial to understand that kenshō is not considered the final destination or full Buddhahood, but rather a significant first step on the path.21

This initial awakening needs to be followed by sustained practice to deepen the insight, integrate it into daily life, and gradually eliminate remaining defilements.21 The Japanese term kenshō is often used interchangeably with satori (悟り), another term signifying comprehension or understanding.21 While often synonymous, some traditions, particularly in the West, make a subtle distinction, using kenshō for an initial experience and satori for a deeper, more complete realization.22 However, historically and in many contemporary Zen circles, they are treated as essentially the same experience.24

The Significance of Initial Insight

In Rinzai Zen, the experience of kenshō holds paramount significance as the very gateway to authentic Buddhist practice.2 It is considered the essential first step that fundamentally alters the practitioner’s understanding of themselves and the universe.4 This initial insight is not a mere intellectual grasp of Buddhist philosophy but a profound and transformative experience that offers a direct glimpse into the true nature of reality.4 It marks a decisive shift in perspective, moving from a conceptual understanding to a direct, experiential knowing.4

Kensho as a Gateway to Practice

Kenshō in the Rinzai tradition is viewed not as an end in itself but as the crucial beginning of a lifelong journey of deepening and embodying this initial awakening.2 It is the opening of a door, providing a taste of enlightenment that motivates and guides further practice.4 This emphasis on a sudden, initial insight aligns with the abrupt and direct teaching style of Linji Yixuan himself, whose “shock” methods were intended to jolt students into a moment of realization.9

In contrast to Sōtō Zen, which tends towards a more gradual approach to enlightenment, Rinzai emphasizes the necessity of this initial breakthrough experience as a foundation for further spiritual development.2 The experience of kenshō can vary greatly in its depth and intensity, ranging from a fleeting glimpse to a more profound and lasting realization.21 Due to this variability and the potential for misinterpretation, the guidance of a qualified Zen teacher is considered essential in Rinzai Zen to help students navigate their experience, confirm the authenticity of their insight, and distinguish it from mere psychological states or delusions.2

The Rigorous Path After Insight: Post-Kensho Training

Deepening and Embodying Awakening

Recognizing kenshō as the initial opening, Rinzai Zen places immense importance on the subsequent phase of post-kensho training.2 The primary aim of this rigorous training is to deepen the initial insight and thoroughly integrate it into every aspect of the practitioner’s life.2 This process involves years of dedicated practice to fully embody the free functioning of wisdom within the activities of daily life.4 It is not enough to simply experience an initial awakening; the insight must permeate one’s thoughts, emotions, and actions, leading to a fundamental transformation of being.2

The Role of Continued Practice

The methods employed in post-kensho training are multifaceted, encompassing continued engagement with core Rinzai practices.2 Continued kōan study remains central, with the teacher assigning progressively more challenging kōans to further dismantle conceptual thought and deepen understanding.2 Intensive zazen continues to be a cornerstone, providing the stable ground for this deeper exploration.2 Furthermore, practitioners are encouraged to bring mindfulness to all their daily activities, integrating the awakened perspective into their work, relationships, and every moment of their lives.2 Throughout this process, the guidance of the Zen teacher remains crucial, providing ongoing support, posing challenging questions, and helping the student navigate the subtle nuances of their deepening realization.2

The Rinzai tradition also utilizes frameworks developed by past masters to guide post-kensho practice. Linji Yixuan himself spoke of the Three Mysterious Gates (三玄三要), representing different stages of understanding and expression of the ultimate truth.21 Dongshan Liangjie (洞山良价) of the Sōtō school, though influential across Zen, is known for his Five Ranks (五位), which map out the interplay between the absolute and relative realms in the process of enlightenment.21 Hakuin Ekaku developed his Four Ways of Knowing, which describe different aspects of the awakened mind.21 Additionally, the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures offer a visual and poetic representation of the various stages on the path to awakening and the return to the world.21 These frameworks illustrate that spiritual development in Rinzai Zen is not a singular event but a continuous process of deepening realization and integration.

Fundamental Practices of Rinzai Zen

Intensive Zazen: Techniques and Emphasis

Zazen (坐禅), or seated meditation, forms a cornerstone of Rinzai Zen practice.2 It is through the consistent and dedicated practice of zazen that practitioners cultivate the stillness and concentration necessary for kenshō and subsequent deepening.65 The typical posture involves sitting with crossed legs, often in the lotus or half-lotus position, with hands folded in a specific mudra (symbolic hand gesture) over the belly, and maintaining an erect yet relaxed spine.2 The focus during zazen is primarily on the breath, allowing it to flow naturally while observing its rhythm.65 Sometimes, techniques such as counting the breaths are employed, particularly for beginners, to help anchor the mind and develop concentration.65

While shikantaza (“just sitting”), a practice of open awareness without a specific object of focus, is recognized within Rinzai Zen, it is generally less emphasized compared to Sōtō Zen, where it is a central practice.2 In Rinzai, shikantaza is often considered a practice for more advanced students who have already had some experience with kenshō and kōan work.2 Integral to the intensive nature of Rinzai practice are sesshin (接心), periods of concentrated meditation that can last for several days.4 These retreats involve extended periods of zazen, often interspersed with walking meditation (kinhin), formal meals, and private interviews with the teacher (sanzen), providing a powerful environment for deepening one’s practice.4

Kōan Introspection: Breaking Down Conceptual Thought

A defining characteristic of Rinzai Zen is the intensive use of kōan (公案), paradoxical riddles, stories, or statements drawn from the dialogues and actions of past Zen masters.2 These are not meant to be solved through logical reasoning but rather are designed to challenge and ultimately break down the practitioner’s habitual patterns of conceptual thought, leading to a direct, intuitive experience of reality.2 The process of engaging with a kōan often leads to a state of intense mental focus and questioning known as “great doubt” (大疑).4 This profound sense of uncertainty and intellectual impasse can, at an unpredictable moment, shatter the limitations of conventional thought, giving rise to the direct, experiential insight of kenshō.70 Rinzai Zen has developed formalized curricula of kōan study, with students typically working through a sequence of kōans under the guidance of their teacher, each designed to address different aspects of Zen understanding.2

Sanzen: The Centrality of the Teacher-Student Relationship

The relationship between a student and a Zen teacher is absolutely central to the practice of Rinzai Zen.2 This relationship is formalized through the practice of sanzen (参禅), also known as dokusan or daisan, which are private interviews between the student and the teacher.2 During sanzen, the student presents their understanding of the assigned kōan to the teacher.2 The teacher, in turn, guides the student’s progress through skillful questioning, challenging their interpretations, and offering “direct pointing” instructions aimed at facilitating the experience of kenshō.2 The teacher plays a crucial role not only in assigning and clarifying kōans but also in recognizing and confirming the student’s kenshō experience and providing guidance for the subsequent post-kensho training.2 This direct, personal interaction is considered indispensable in Rinzai Zen for navigating the often subtle and challenging path to awakening.4

Other Integral Practices: Kinhin, Samu, and Chanting

Beyond zazen, kōan study, and sanzen, Rinzai Zen incorporates other practices that support the overall cultivation of mindfulness and awakening [User Query]. Kinhin (経行), or walking meditation, is typically practiced between periods of zazen. It involves slow, mindful walking, often in a circle, with a focus on the sensation of walking and the breath, helping to maintain awareness in movement.2 Samu (作務) refers to mindful work or physical labor undertaken with full awareness and presence.2 Whether it is cleaning, gardening, or other tasks, samu provides an opportunity to integrate the principles of Zen practice into everyday activities.74 Chanting 2 of Buddhist sutras and dharanis (mantric phrases) is also a significant element of Rinzai practice. Chanting can cultivate concentration, devotion, and a deeper connection to the teachings of the Buddha.65 These diverse practices collectively contribute to a holistic training that extends beyond the meditation cushion and into all aspects of the practitioner’s life.

A Distinctive Style: Martial Spirit and Samurai Connections

Rinzai Zen is often characterized by a distinctive “martial” or “sharp” style.2 This stylistic attribute can be traced back to the dynamic and iconoclastic teaching methods of its founder, Linji Yixuan, known for his directness and use of shouts and blows to jolt students into awakening.32 However, the “martial” aspect of Rinzai Zen is not necessarily about physical combat but rather reflects a rigorous, disciplined, and often intense approach to spiritual training.2 Historically, Rinzai Zen had strong ties to the samurai class in Japan.2

As the samurai rose to power during the Kamakura period, they were drawn to Rinzai Zen’s emphasis on direct experience, spontaneity, and its ability to cultivate mental fortitude and fearlessness in the face of death.2 The patronage of the warrior class significantly shaped the cultural image of Rinzai Zen in Japan, contributing to its reputation as a more rigorous and disciplined path compared to other schools.2 This historical association helped solidify Rinzai’s distinct identity and influence within Japanese society.

Rinzai Zen in Modern Japan: Organization and Branches

In modern Japan, Rinzai Zen does not exist as a single, centralized entity but is organized into 15 distinct branches, each associated with its own head temple.1 These branches represent organizational divisions arising from temple history and teacher-student lineages, rather than fundamental differences in practice, although minor variations in kōan handling may exist.44 The head temples preside over networks comprising thousands of affiliated temples, monasteries, and a nunnery.44

Table: The Fifteen Branches of Rinzai Zen in Modern Japan

| Branch Name (Head Temple) | Founding Period/Figure (if known) | Location |

| Kennin-ji (建仁寺) | 1202 | Kyoto |

| Tōfuku-ji (東福寺) | 1236 / Enni Ben’en (圓爾辯圓) | Kyoto |

| Kenchō-ji (建長寺) | 1253 | Kamakura |

| Engaku-ji (円覚寺) | 1282 | Kamakura |

| Nanzen-ji (南禅寺) | 1291 / Musō Soseki (夢窓疎石) | Kyoto |

| Kokutai-ji (国泰寺) | 1300 | Toyama |

| Daitoku-ji (大徳寺) | 1315 / Shūhō Myōchō (宗峰妙超) | Kyoto |

| Kōgaku-ji (向嶽寺) | 1380 | Yamanashi |

| Myōshin-ji (妙心寺) | 1342 / Kanzan Egen (関山慧玄) | Kyoto |

| Tenryū-ji (天龍寺) | 1339 / Musō Soseki (夢窓疎石) | Kyoto |

| Eigen-ji (永源寺) | 1361 | Shiga |

| Hōkō-ji (方広寺) | 1384 | Shizuoka |

| Shōkoku-ji (相国寺) | 1392 | Kyoto |

| Buttsū-ji (佛通寺) | 1397 | Hiroshima |

| Kōshō-ji (興聖寺) | 1603 / Koō Enni (虚応円耳) | Kyoto |

Among these branches, the Myōshin-ji (妙心寺) branch stands out as the largest and most influential.2 Its head temple, located in Kyoto, was founded in 1342 by Kanzan Egen (関山慧玄), a significant figure in the Ōtōkan lineage.44 The Myōshin-ji school encompasses approximately 3,400 temples across Japan, making it roughly as large as all the other Rinzai branches combined.44 Within the Myōshin-ji branch, there are four main administrative divisions: Ryōsen-ha (龍泉派), Tōkai-ha (東海派), Reiun-ha (靈雲派), and Shotaku-ha (聖澤派).89

Furthermore, Hanazono University, a major institution for Buddhist studies, was established by the Myōshin-ji branch in 1872 and remains a significant center for Rinzai education.2 The decentralized nature of Rinzai Zen in modern Japan, with its numerous independent branches, contrasts with the more centralized organizational structure found in Soto Zen.2 The sheer size and influence of the Myōshin-ji branch underscore its dominant role in shaping the contemporary landscape of Rinzai Zen practice and scholarship.

Rinzai Zen in Relation to Other Schools: A Comparison with Soto Zen

While both Rinzai and Sōtō are major schools of Zen Buddhism that originated in China and flourished in Japan, they exhibit distinct differences in their emphasis, practice, and style.2 A primary distinction lies in their approach to enlightenment. Rinzai Zen is known for its emphasis on kenshō, the sudden awakening of transcendental wisdom.1 In contrast, Sōtō Zen emphasizes a more gradual path to enlightenment through the consistent practice of shikantaza, or “just sitting” meditation.1 Their core practices also differ significantly. Rinzai Zen heavily utilizes kōan introspection as a central tool to break down conceptual thought and facilitate direct experience.2

While kōans are not entirely absent in Sōtō Zen, they are less central to the practice, which prioritizes the silent, objectless awareness of shikantaza.2 Stylistically, Rinzai Zen is often described as more “martial” or “sharp” in its approach, reflecting the spirit of its founder and its historical ties to the samurai class.2 Sōtō Zen, on the other hand, is often characterized as more gentle, quiet, and even rustic in its spirit.2 Organizationally, Rinzai Zen in modern Japan is marked by its decentralized structure with 15 independent branches, while Sōtō Zen has a more centralized organizational framework.2 Historically, Rinzai Zen enjoyed significant patronage from the samurai and ruling elite, whereas Sōtō Zen garnered a broader following among the general populace.3 Despite these differences, both schools ultimately aim for the same goal of liberation and offer distinct yet valuable pathways for spiritual seekers.

From China to Japan: The Transmission and Development of Rinzai

The transmission of the Linji school of Chan Buddhism from China to Japan was a gradual process involving several key figures and periods of development.1 Myōan Eisai (明菴栄西, 1141-1215) is widely recognized as the first monk to firmly establish a Rinzai lineage in Japan during the Kamakura period (1185-1333).1 After traveling to China and studying Tendai Buddhism, Eisai returned to Japan and, following a second trip to China where he received initiation into the Linji school, he established Shōfuku-ji, Japan’s first Zen temple, and later Kennin-ji in Kyoto.2 Decades later, Nanpo Shōmyō (南浦紹明, 1235-1308), who also studied Linji teachings in China, founded the Japanese Ōtōkan lineage, which became the most influential and the only surviving branch of the Rinzai school in Japan.1

During the Muromachi period, influential Japanese Zen masters like Shūhō Myōchō (宗峰妙超, 1282-1337), also known as Daitō Kokushi, and Musō Soseki (夢窓疎石, 1275-1351) further solidified Rinzai’s identity in Japan, even without traveling to China for study.2 The establishment of the Five Mountain System (Gozan 五山), a network of state-supported Zen temples, also played a significant role in the propagation and institutionalization of Rinzai Zen.1 By the 18th century, the Rinzai school had experienced a period of decline, but it was revitalized by the efforts of Hakuin Ekaku (白隠慧鶴, 1686-1769), whose vigorous approach to koan practice and focus on awakening brought about a lasting revival that continues to shape Rinzai Zen today.1 The transmission of Rinzai Zen to Japan was therefore a complex interplay of dedicated individuals and evolving socio-political landscapes, resulting in a uniquely Japanese expression of the Chinese Chan tradition.

The Far-Reaching Influence of Rinzai Zen on Japanese Culture

Rinzai Zen’s impact on Japanese culture extends far beyond the realm of religion, permeating various aspects of art, literature, philosophy, and the very fabric of societal conduct.1

Impact on Art and Literature

The principles of Rinzai Zen, such as simplicity, spontaneity, and the appreciation of the present moment, profoundly influenced Japanese artistic expression.1 Ink wash painting (sumi-e 墨絵), with its minimalist aesthetic and emphasis on capturing the essence of a subject with swift, decisive brushstrokes, became closely associated with Zen Buddhism.76 Similarly, calligraphy (shodō 書道) was elevated to a spiritual practice, with the act of writing seen as a form of meditation, reflecting the Zen emphasis on mindfulness and direct experience.80

Zen’s influence is also evident in the design of Japanese gardens, particularly the dry landscape gardens (karesansui) which embody Zen principles of simplicity, austerity, and harmony with nature, created for contemplation and meditation.80 In the realm of literature, Zen’s impact can be seen in the development of haiku poetry, a concise form that captures fleeting moments of insight and often reflects the Zen appreciation for the natural world and the present moment.2 Furthermore, the aesthetic principles of wabi-sabi (侘寂), finding beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and simplicity, are deeply rooted in Zen philosophy and have shaped Japanese artistic sensibilities for centuries.76

Philosophical Underpinnings

Rinzai Zen significantly contributed to the philosophical landscape of Japan, emphasizing direct experience and intuition over intellectual understanding.1 The cultivation of mindfulness and presence in the moment, central to Zen practice, has influenced Japanese approaches to self-awareness and engagement with the world.82 The concept of “no-mind” (mushin 無心), a state of mind free from conscious thought and judgment, is also an important philosophical contribution of Zen, encouraging spontaneity and intuitive action.80

Connection to the Samurai Code of Conduct

Perhaps one of the most notable cultural impacts of Rinzai Zen in Japan is its profound influence on the samurai code of conduct, known as bushidō (武士道).2 The warrior class found resonance in Zen’s emphasis on discipline, self-control, and mental clarity, qualities essential for the life of a samurai.80 Zen’s focus on the impermanence of life and the acceptance of death without fear aligned perfectly with the samurai’s readiness to face mortality in battle.82 The principles of mindfulness and acting decisively in the present moment, cultivated through Zen meditation, were also highly valued in the samurai’s way of life.82 This intertwining of Zen philosophy and the samurai ethos had a lasting impact on Japanese ethics, aesthetics, and traditional arts.82

Key Figures in the History of Rinzai Zen

The history of Rinzai Zen is marked by the contributions of numerous influential masters who shaped its teachings and practices across centuries and continents.

Influential Masters in China

Linji Yixuan (臨済義玄) (d. 866 CE) stands as the foundational figure, whose dynamic and iconoclastic approach defined the core spirit of the school.2 His teacher, Huangbo Xiyun (黃檗希運) (d. ca. 850), played a crucial role in Linji’s early training and enlightenment.6 Later, during the Song Dynasty, Dahui Zonggao (大慧宗杲, 1089-1163) significantly shaped Rinzai practice through his emphasis on kōan study and the generation of “great doubt”.2

Pioneers and Reformers in Japan

The transmission of Rinzai Zen to Japan owes much to Myōan Eisai (明菴栄西, 1141-1215), who is credited with establishing the first lasting lineage in the late 12th and early 13th centuries.1 Nanpo Shōmyō (南浦紹明, 1235-1308) further cemented Rinzai’s presence and founded the influential Ōtōkan lineage, which remains the only surviving branch today.1 Shūhō Myōchō (宗峰妙超, 1282-1337) founded Daitoku-ji, a highly influential Rinzai temple in Kyoto.2 Musō Soseki (夢窓疎石, 1275-1351) was another pivotal figure, renowned not only as a Zen master but also as a celebrated garden designer and spiritual advisor to both emperors and shoguns.2

Perhaps the most significant figure in the revitalization of Rinzai Zen was Hakuin Ekaku (白隠慧鶴, 1686-1769), whose reforms in the 18th century established the foundation for modern Rinzai practice, emphasizing rigorous koan study and making Zen more accessible.1 In more recent times, figures like Ōmori Sōgen, Sōkō Morinaga, Shodo Harada, Eshin Nishimura, Keidō Fukushima, and D.T. Suzuki have been influential in preserving and propagating Rinzai Zen.2 Notably, D.T. Suzuki played a pivotal role in introducing Zen Buddhism, including Rinzai, to Western audiences through his extensive writings and lectures.2

Rinzai Zen in the Western World: Interpretations and Adaptations

The transmission of Rinzai Zen to the Western world has led to various interpretations and adaptations of its practice and philosophy.2 Figures like D.T. Suzuki played a crucial role in introducing Zen to the West, often emphasizing its experiential and non-intellectual aspects, which resonated with Western spiritual seekers.2 This led to the emergence of Western Rinzai teachers and Zen centers across the Americas and Europe.2 However, the transmission of Rinzai Zen to the West has also faced challenges. Cultural differences, varying understandings of Buddhist concepts like rebirth and karma, and the tendency towards secularization have led to diverse interpretations and adaptations.2

Some Western interpretations have focused more on the psychological and therapeutic benefits of meditation, while others have sought to maintain the traditional rigor and emphasis on kenshō and post-kensho training.134 The adaptation of monastic practices for lay practitioners in the West has also been a significant aspect of this transmission.129 Despite these adaptations and challenges, Rinzai Zen continues to attract a growing number of practitioners in the West, drawn to its direct path to awakening and its emphasis on personal experience.2

The Enduring Legacy and Practice of Rinzai Zen

Rinzai Zen, originating from the dynamic teachings of Linji Yixuan in 9th-century China, has evolved into a significant and influential school of Zen Buddhism. Characterized by its emphasis on the sudden awakening of kenshō, its rigorous post-kensho training, and its core practices of intensive zazen and kōan introspection, Rinzai Zen offers a direct and often challenging path to understanding one’s true nature. The central role of the Zen teacher in guiding students through the intricacies of this practice remains a defining feature of the tradition.

Historically intertwined with the samurai class in Japan, Rinzai Zen developed a distinctive “martial” spirit that reflects its disciplined and focused approach. While organized into 15 independent branches in modern Japan, with the Myōshin-ji branch being the largest, Rinzai Zen continues to adapt and find new expressions in the Western world. Its enduring legacy lies in its unwavering commitment to the transformative power of direct experience and its profound influence on Eastern and increasingly Western spirituality.

Works cited

- Rinzai | Zen, Japan, Meditation | Britannica, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Rinzai

- Rinzai school – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rinzai_school

- Rinzai/Linji Zen – Learn Religions, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.learnreligions.com/rinzai-zen-449854

- Lesson 4: Soto and Rinzai Zen Schools | Clear Way Zen, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.clearwayzen.ca/for-beginners/lesson-4-soto-and-rinzai-zen-school/

- Lesson-4-Rinzai-and-Soto-Zen.pdf, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.clearwayzen.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Lesson-4-Rinzai-and-Soto-Zen.pdf

- Linji Yixuan – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linji_Yixuan

- Buddhism in Early Tang | Encyclopedia.com, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/buddhism-early-tang

- Buddhism in the Tang (618–906) and Song (960–1279) Dynasties – Education, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://education.asianart.org/resources/buddhism-in-the-tang-618-906-and-song-960-1279-dynasties/

- Lin-chi – New World Encyclopedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Lin-chi

- Seeing Into One’s Own Nature By Linji Yixuan Introduction – Asia for Educators, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/linji_yixuan_seeing_own_nature.pdf

- Chan Buddhism: The Classical Period, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://tfreeman.net/resources/Phil-430/Linji.pdf

- Kill the Buddha – RSSB Satsangs & Essays, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://rssb.org/essay130.html

- Línjì Yìxuán – Tibetan Buddhist Encyclopedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://tibetanbuddhistencyclopedia.com/en/index.php?title=L%C3%ADnj%C3%AC_Y%C3%ACxu%C3%A1n

- The Zen Teachings of Master Lin-Chi by Línjì Yìxuán | Goodreads, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/354936.The_Zen_Teachings_of_Master_Lin_Chi

- Linji – The True Person Without Rank – Buddhism: The Way of Emptiness, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://buddhism-thewayofemptiness.blog.nomagic.uk/linji-the-true-person-without-rank/

- Linji school – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linji_school

- The Linji Lu and the Creation of Chan Orthodoxy: The Development of Chan’s Records of Sayings Literature – Amazon.com, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Linji-Creation-Chan-Orthodoxy-Development/dp/0195329570

- The Linji Lu and the Creation of Chan Orthodoxy – Albert Welter – Oxford University Press, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-linji-lu-and-the-creation-of-chan-orthodoxy-9780195329575

- Buddhism – Linji and the Linjilu – Oxford Bibliographies, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/abstract/document/obo-9780195393521/obo-9780195393521-0185.xml

- The Record of Linji – UH Press, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://uhpress.hawaii.edu/title/the-record-of-linji/

- Kenshō – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kensh%C5%8D

- Kenshō – Encyclopedia of Buddhism, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://encyclopediaofbuddhism.org/wiki/Kensh%C5%8D

- ‘Kensho’ in Zen, ‘Recognition’ in Tibetan Dharma | by Michael Erlewine – Medium, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://medium.com/@MichaelErlewine/kensho-in-zen-recognition-in-tibetan-dharma-a8f365cc9b06

- What *exactly* are satori and kensho? – Dharma Wheel, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.dharmawheel.net/viewtopic.php?t=44949

- Theravada’s Equivalent of Zen’s Kensho? – Dhamma Wheel Buddhist Forum, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.dhammawheel.com/viewtopic.php?t=6109

- Satori – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satori

- Kensho: A Glimpse Into Awakening. – The Tattooed Buddha, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://thetattooedbuddha.com/2015/12/07/kensho-a-glimpse-into-awakening/

- The Kenshō Moment- A Glimpse Of The Mystic You – Thrive Global, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://community.thriveglobal.com/the-kensho-moment-a-glimpse-of-the-mystic-you/

- Kenshō – LessWrong, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/tMhEv28KJYWsu6Wdo/kensh

- The Rinzai Zen Way: A Guide to Practice, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.shambhala.com/the-rinzai-zen-way-15201.html

- Our Practice | The Oxford Zen Centre, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://oxfordzencentre.org.uk/history-of-sanbo-zen/our-practice/

- Rinzai Gigen and Shogun Zen – Still Sitting Meditation Supply, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.stillsitting.com/rinzai-gigen/

- Satori or kensho? Confused by recent experience : r/Buddhism – Reddit, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Buddhism/comments/sodn2n/satori_or_kensho_confused_by_recent_experience/

- LINGUISTIC AND OTHER CHALLENGES IN RESEARCHING TRANSCENDENT PHENOMENA: CONSIDERATIONS FROM WITTGENSTEIN AND BUDDHIST PRACTICE, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-45-13-01-075.pdf

- Mechanics of Soto Zen/Kensho/Enlightenment : r/zenbuddhism – Reddit, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/zenbuddhism/comments/l9acv1/mechanics_of_soto_zenkenshoenlightenment/

- 200 – Story of My Spiritual Journey Part 4: Enlightenments – The Zen Studies Podcast, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://zenstudiespodcast.com/enlightenments/

- Teacher & Student – Clear Way Zen, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.clearwayzen.ca/about-zen/teacher-student/

- Do you think Kensho is common in zen? : r/zenbuddhism – Reddit, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/zenbuddhism/comments/1dza7dq/do_you_think_kensho_is_common_in_zen/

- Hakuin on Kensho: The Four Ways of Knowing – Amazon.com, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Hakuin-Kensho-Four-Ways-Knowing/dp/1590303776

- Shido Bunan on post-kensho training : r/zen – Reddit, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/zen/comments/62vbyl/shido_bunan_on_postkensho_training/

- The Possibility and Importance of Awakening in Zen Buddhism – Tricycle, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://tricycle.org/article/zen-awakening/

- The Rinzai Zen Way – Innercraft, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.inner-craft.com/courses/the-rinzai-zen-way/

- The Rinzai Zen Way: A Guide to Practice, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.shambhala.com/the-rinzai-zen-way.html

- Rinzai Zen – Encyclopedia of Buddhism, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://encyclopediaofbuddhism.org/wiki/Rinzai_Zen

- Working with a Teacher – Dharma Wheel, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.dharmawheel.net/viewtopic.php?t=11893

- Linji Yixuan – Encyclopedia of Buddhism, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://encyclopediaofbuddhism.org/wiki/Linji_Yixuan

- Linji’s Three Phrases : r/zen – Reddit, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/zen/comments/fkp3s2/linjis_three_phrases/

- Subitism – Tibetan Buddhist Encyclopedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://tibetanbuddhistencyclopedia.com/en/index.php/Subitism

- Zen | Teachings | Buddhism & Healing – Red Zambala, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://buddhism.redzambala.com/buddhism/traditions/zen-teachings.html

- Dongshan Liangjie – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dongshan_Liangjie

- Five Ranks – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five_Ranks

- Dongshan Liangjie – Encyclopedia of Buddhism, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://encyclopediaofbuddhism.org/wiki/Dongshan_Liangjie

- The Five Ranks in Buddhism. – The Tattooed Buddha, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://thetattooedbuddha.com/2015/08/18/the-five-ranks-in-buddhism/

- Dongshan’s Five Ranks: Keys to Enlightenment by Bolleter, Ross(May 13, 2014) Paperback, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Dongshans-Five-Ranks-Enlightenment-Paperback/dp/B013RPADMO

- Hakuin Ekaku – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hakuin_Ekaku

- Hakuin on Kensho: The Four Ways of Knowing – 9781590303771 – Shambhala Publications, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.shambhala.com/hakuin-on-kensho-686.html

- Hakuin Ekaku: A Reader’s Guide – Shambhala Pubs, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.shambhala.com/hakuin-ekaku-c-1685-1768/

- Hakuin on Kensho: The Four Ways of Knowing – Everand, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.everand.com/book/770612339/Hakuin-on-Kensho-The-Four-Ways-of-Knowing

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Bulls#:~:text=Ten%20Bulls%20or%20Ten%20Ox,to%20enact%20wisdom%20and%20compassion

- Ten Bulls – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Bulls

- The Oxherding Pictures – 2022 – Seattle Insight Meditation, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://seattleinsight.org/the-oxherding-pictures-2022/

- The Ten Oxherding Pictures – Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://tricycle.org/magazine/ten-oxherding-pictures/

- Searching for the Ox: The Path to Enlightenment in 10 Pictures – Lion’s Roar, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.lionsroar.com/searching-for-the-ox-the-path-to-enlightenment-in-10-pictures/

- 78 – The Ten Oxherding Pictures: Stages of Practice When You’re Going Nowhere, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://zenstudiespodcast.com/ten-oxherding-pictures/

- How To Practice Zen – Zen Studies Society, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://zenstudies.org/teachings/how-to-practice/

- Zazen – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zazen

- Rinzai Zen Lineage — Daiyuzenji Rinzai Zen Temple, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://daiyuzenji.org/history

- Zen Training – Daiyuzenji Rinzai Zen Temple, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://daiyuzenji.org/zentraining

- Koan – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koan

- Tried Koan Introspection Yet? – RAAS Health, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://raashealth.in/2023/11/25/tried-koan-introspection-yet/

- Koan – (Intro to Buddhism) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations | Fiveable, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-buddhism/koan

- I don’t understand “koan”, “satori”, and “kensho” : r/zen – Reddit, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/zen/comments/wd78yt/i_dont_understand_koan_satori_and_kensho/

- Zen Koan Pedagogy: A Spiritual Approach to Management Education – ResearchGate, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365010812_Zen_Koan_Pedagogy_A_Spiritual_Approach_to_Management_Education

- Zen Buddhism: A Practice of learning from Masters – Original Buddhas, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.originalbuddhas.com/blog/zen-buddhism

- The goal/stages/results of Zen meditation? – Dharma Wheel, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.dharmawheel.net/viewtopic.php?t=9351

- Zen Buddhism – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/zen-buddhism

- Rinzai Zen – Korinji, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.korinji.org/rinzai-zen

- A Not-So Brief History of Zen and Samurai – Gleanings in Buddha-Fields, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://nembutsu.cc/2024/02/23/a-not-so-brief-history-of-zen-and-samurai/

- Rinzai – New World Encyclopedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Rinzai

- Art and Architecture in Japan Unit 5 – Kamakura: Zen’s Impact on Japanese Art – Fiveable, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/art-and-architecture-in-japan/unit-5

- Premodern Japanese Zen – Buddhism – Oxford Bibliographies, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/abstract/document/obo-9780195393521/obo-9780195393521-0182.xml

- Rise of Zen Buddhism and its influence | History of Japan Class Notes – Fiveable, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/history-japan/unit-3/rise-zen-buddhism-influence/study-guide/jlhqVGftaQs09BsI

- From Temples to Dojos: Zen’s Influence on Samurai and the Martial Arts | BUDO JAPAN, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://budojapan.com/culture-event/241015/

- Buddhism and the Samurai | Denver Art Museum, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/blog/buddhism-and-samurai

- Power and Serenity: how religion and belief influenced the way of the Samurai – Western Oregon University, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://cdn.wou.edu/history/files/2015/08/Joe-Lovatt-HST-499.pdf

- Reconsidering Zen, Samurai, and the Martial Arts – Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://apjjf.org/2016/17/benesch

- Head Temples – Rinzai-Obaku zen, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://zen.rinnou.net/head_temples/index.html

- Rinzai school | Dictionary of Buddhism, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/dic/Content/R/49

- Head Temples – Myoshinji Temple – Rinzai-Obaku zen, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://zen.rinnou.net/head_temples/01myoshin.html

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My%C5%8Dshin-ji

- Miyoshin-ji | Traditional Kyoto, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://traditionalkyoto.com/temples-shrines-and-palaces/temples/miyoshinji/

- Japanese Zen – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_Zen

- What’s the major differences between Rinzai and Soto Zen? : r/Buddhism – Reddit, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Buddhism/comments/9cbzgf/whats_the_major_differences_between_rinzai_and/

- Chan, Linji – The Pluralism Project, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://pluralism.org/chan-linji

- Linji Buddhism · Middle Land Chan Buddhist Monastery – Religious and Ritual Sites in Los Angeles, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://laritualsites.omeka.net/exhibits/show/middle-land-chan/buddhism/linji

- thezensite:The Textual History of the Linji lu, accessed on April 1, 2025, http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/HistoricalZen/welter_Linji.html

- Rinzai Zen – Shambhala Pubs, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.shambhala.com/rinzai-zen/

- fiveable.me, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-buddhism/myoan-eisai#:~:text=My%C5%8Dan%20Eisai%20is%20recognized%20for,and%20integrated%20into%20local%20practices.

- Chapter 6 The Anatomical Architecture of Myōan Eisai in: Buddhism and the Body – Brill, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004544925/BP000015.xml

- Eisai – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eisai

- Myōan eisai – (Intro to Buddhism) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations | Fiveable, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-buddhism/myoan-eisai

- Nanpo Shōmyō – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanpo_Sh%C5%8Dmy%C5%8D

- Shūhō Myōchō – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shuho_Myocho

- Calligraphy by Daitō Kokushi (Shūhō Myōchō): Buddhist teachings (known as the Kogarashi bokuseki), accessed on April 1, 2025, https://emuseum.nich.go.jp/detail?langId=en&webView=&content_base_id=100008&content_part_id=000&content_pict_id=0

- Calligraphy: Words of Religious Enlightenment – MOA MUSEUM OF ART, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.moaart.or.jp/en/collections/104/

- Daitoku-ji – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daitoku-ji

- Calligraphy – MOA MUSEUM OF ART, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.moaart.or.jp/en/collections/105/

- Musō Soseki – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mus%C5%8D_Soseki

- Musō Soseki – The Wisdom Experience, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://wisdomexperience.org/content-author/muso-soseki/

- Musō Sōseki | Encyclopedia.com, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/muso-soseki

- The Limitations Of Core Rinzai Zen – Andrew Taggart, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://andrewjtaggart.com/2020/10/07/the-limitations-of-core-rinzai-zen/

- Rinzai Zen Buddhist Meditation – Deeper Japan, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://deeperjapan.com/hiroshima/zazen-experience-in-ranzai-zen-temple

- The Zen Masters of the Rinzai Tradition – Buddhistdoor Global, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/the-zen-masters-of-the-rinzai-tradition/

- Who are some prominent figures in Zen Buddhism? – Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://tricycle.org/beginners/buddhism/historical-figures-in-zen/

- Hakuin – New World Encyclopedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Hakuin

- Hakuin | Zen master, Japanese calligraphy, Rinzai school – Britannica, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hakuin

- The Essential Teachings of Zen Master Hakuin – Terebess, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://terebess.hu/zen/HakuinWaddell.pdf

- Hakuin | Encyclopedia.com, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/hakuin

- Zen: Contemporary Masters & Teachings – Buddhism – Research Guides, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://research.lib.buffalo.edu/buddhism/zen-contemporary-masters

- Zen: Soto, Rinzai and Sanbo Zen, Part 1 of 2 – Mountain Cloud Zen Center, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.mountaincloud.org/zen-soto-rinzaihttpswww-mountaincloud-orgp7512previewtrue-and-sanbo-zen-part-1-of-2/

- Japanese Zen | Editor’s Column “The Path of Japanese Crafts” Part1: Japanese Aesthetic Sense | Insight | KOGEI STANDARD | Online Media for Japanese Crafts, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.kogeistandard.com/insight/serial/editor-in-chief-column-kogei/zen/

- Full article: The influence of Zen Buddhism and ink wash painting on Japanese gardens during the medieval Japan – Taylor & Francis Online, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13467581.2024.2441919?src=

- What is Zen? (3) How Zen influenced traditional Japanese wabi sabi art – – Zero = abundance, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.interactiongreen.com/home-2/zero/zen-art-wabi-sabi/

- Fierce Practice, Courageous Spirit, and Spiritual Cultivation: The Rise of Lay Rinzai Zen in Modern Japan – DukeSpace, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/items/7c186a0c-de19-4287-bc0d-1d378c0a3004

- The Record of Linji by Línjì Yìxuán – Goodreads, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3861639

- Chan Buddhism During the Times of Venerable Master Yixuan and Venerable Master Hsing Yun, accessed on April 1, 2025, http://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-BJ010/bj010609644.pdf

- Hongzhou school – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hongzhou_school

- ABSTRACT THE WAN LING RECORD OF CHAN MASTER HUANGBO DUANJI: A HISTORY AND TRANSLATION OF A TANG DYNASTY TEXT Jeffrey M. Leahy Ma – Terebess, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://terebess.hu/zen/duan.pdf

- i v Fierce Practice, Courageous Spirit, and Spiritual Cultivation: The Rise of Lay Rinzai Zen in Modern Japan by Rebecca Mendels – Terebess, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://terebess.hu/zen/mesterek/Mendelson.pdf

- Zen Studies Society: An American Rinzai Zen Community, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://zenstudies.org/

- Zen: Soto, Rinzai and Sanbo Zen Part 2 of 2 – Mountain Cloud Zen Center, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.mountaincloud.org/zen-soto-rinzai-and-sanbo-zen-part-2-of-2/

- Zen in the United States – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zen_in_the_United_States

- From Elite Zen to Popular Zen: Readings of Text and Practice in Japan and the West – The Zen Site, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/Philosophical/From_Elite_Zen_to_Popular_Zen.pdf

- Zen (school) | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/religion-and-philosophy/zen-school

- D. T. Suzuki – Wikipedia, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D._T._Suzuki

- Can someone please explain to me what “westernized” Zen is? : r/Buddhism – Reddit, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Buddhism/comments/1972e3l/can_someone_please_explain_to_me_what_westernized/

- The Zen Teaching of Rinzai – thezensite, accessed on April 1, 2025, http://www.thezensite.com/ZenTeachings/Translations/Teachings_of_Rinzai.pdf

- Zen Buddhism: History, Beliefs, and American Adaptation | Free Essay Example, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://studycorgi.com/zen-buddhism-in-america/

- Anti-intellectualism in Western Zen – Page 2 – Dharma Wheel, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.dharmawheel.net/viewtopic.php?t=41050&start=20

- What’s wrong with Rinzai? – Forums – Treeleaf Zendo, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://forum.treeleaf.org/forum/treeleaf/treeleaf-community-topics-about-zen-practice/archive-of-older-threads/958-what-s-wrong-with-rinzai

- Soto and inka shomei – Bokusan zenji case – Dharma Wheel, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.dharmawheel.net/viewtopic.php?t=33809

- How Rinzai Zen Came to America – Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://tricycle.org/article/ruth-fuller-sasaki-zen/

- How have Westerners adapted Zen to suit their own needs? – Mollie Magill, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://molliemagill.wordpress.com/how-have-westerners-adapted-zen-to-suit-their-own-needs/

- Shaku Sōen (1860-1919) and Rinzai Zen in modern Japan, 1868-1919 – University of Iowa, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://iro.uiowa.edu/esploro/outputs/doctoral/Shaku-S%C5%8Den-1860-1919-and-Rinzai-Zen/9983776774002771

- The American Way of Zen: How It Arrived and Why It Thrived – Articles by MagellanTV, accessed on April 1, 2025, https://www.magellantv.com/articles/the-american-way-of-zen-how-it-arrived-and-why-it-thrived