Zen’s Expansive Embrace

Zen is often narrowly perceived as a solitary practice confined to seated meditation, or zazen. However, this understanding captures only a fraction of its profound depth. At its core, Zen is a comprehensive “path that must be studied, practiced, and actualized,” one that extends meditative principles and awareness into “every aspect of daily life”.1 This includes seemingly mundane activities such as walking, chanting, eating, and working, transforming them into opportunities for profound spiritual engagement.1

Beyond the Mat: Redefining Zen Practice

The essence of Zen lies not in adherence to dogma but in “experiential insight”.5 It is fundamentally “not based on beliefs or religious doctrine”.1 This emphasis on direct experience over intellectual assent or creed is a pivotal characteristic, making Zen uniquely adaptable and appealing across diverse cultural and philosophical landscapes. The focus on personal verification through lived experience allows Zen to resonate with individuals seeking practical tools for well-being and clarity, regardless of their religious background. This approach facilitates its integration into various aspects of modern life, from professional settings to personal relationships, as it offers a framework for direct engagement with reality rather than a prescribed set of beliefs.

The Ancient Roots of Everyday Zen

The practice of zazen, considered the “heart of the practice” 2, traces its origins back to the Buddha himself, approximately 2,600 years ago, transmitted through an unbroken lineage of masters “from mind to mind” (I shin den shin).2 This ancient lineage underscores the depth and continuity of Zen wisdom. A significant historical development that broadened Zen’s scope was the teaching of Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch of Zen in China. Huineng famously emphasized “seeing into one’s own Nature” 5, and critically, he asserted that this realization should occur “while the self is in the midst of action”.5 This perspective fundamentally challenges any notion that spiritual awakening is confined to passive meditation or monastic seclusion. Instead, it posits that profound insight is accessible and manifest within the dynamic flow of everyday activities. This philosophical shift means that every moment, every interaction, and every task can become a direct path to awakening, making Zen profoundly relevant and applicable to the lives of householder practitioners who engage fully with the world.6

Introducing the Five Styles of Zen: A Framework for Understanding

To better understand the diverse motivations and varying depths of Zen practice, some teachers categorize it into “Five Styles of Zen” [User Query]. This framework, first articulated by Kuei-feng Tsung-mi (780-841), a prominent C’han master and the fifth Ancestor of the Hua Yen tradition in Tang dynasty China, provides a nuanced lens through which to examine different approaches to the path.6 Later, influential teachers like Yasutani Roshi also presented a similar classification in their introductory lectures for students.10 These styles categorize Zen practices based on their “substance and purpose” 13, offering a valuable “map” for practitioners.12 This historical and pedagogical classification is not merely an academic exercise; it serves as a crucial guide for individuals to understand their own motivations and the potential trajectory of their practice. In an era where many individuals seek spiritual paths but may lack the traditional “faith and burning zeal” of past practitioners, this framework provides a theoretical understanding that can help them navigate the complexities of Zen, avoiding “hazardous bypaths of the occult, the psychic, or the superstitious”.12 It allows for a structured exploration of Zen’s varied expressions, from secular benefits to profound spiritual realization.

The Heart of Zen: Zazen and Its Foundational Role

While the report will delve into Zen’s expansive reach beyond formal sitting, it is essential to first establish zazen as the foundational wellspring from which all other practices flow. This section details the mechanics and deeper purpose of this core meditative discipline.

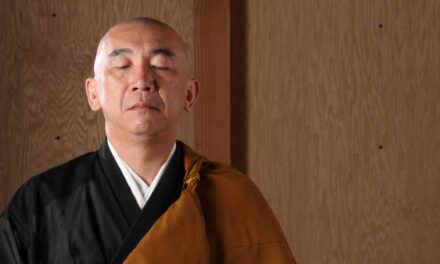

The Essence of Just Sitting: Posture, Breath, and Mind

Zazen, or seated meditation, is universally recognized as the “heart of the practice” within Zen.2 It is characterized as a “sitting meditation without an object” 2, or simply “just sitting” (shikantaza).10 This practice demands motivation, patience, discipline, and dedication, cultivated through consistent engagement.1

The practice is built upon three fundamental elements: “an erect sitting posture, correct control of breathing, and concentration (unification) of mind”.13

- Posture: The physical posture in zazen is meticulously defined. Practitioners sit upright and attentive, often facing a wall.3 Various leg positions are adopted based on individual flexibility, including full lotus (Kekkafuza), half lotus (Hankafuza), Burmese, or kneeling (Seiza).1 For those unable to sit on the floor, a meditation bench or a properly adjusted chair can be used.1 A straight spine, with the chin slightly tucked in, ensures an erect yet relaxed posture, allowing tension to fall away from the shoulders.1 Hands are typically held in a specific mudra, commonly with the right hand holding the left thumb, covered by the left hand, resting at waist level.1 Eyes remain “half-open, with the gaze softly resting on the floor in front”.1 This half-open gaze is deliberate, designed to prevent dullness or falling into a stupor, maintaining a state of alert awareness.17

- Breath: The breath serves as the initial anchor for attention. It should be allowed to flow “softly and naturally”.1 Techniques to support concentration include counting exhalations from one to ten, returning to one when the mind wanders 1, or simply observing the breath (anapanasati or zuisokukan).3 The emphasis is on “feeling the breath instead of watching or following it” 3, promoting a direct, embodied experience.

- Mind: The ultimate aim for the mind in zazen is “suspending all judgemental thinking and letting words, ideas, images and thoughts pass by without getting involved in them”.10 Practitioners are encouraged to become “an observer,” allowing thoughts to “run their course” without force or resistance.3 The mind is not meant to be emptied or rested in a trance-like state, but rather to establish a “base, a foundation, or a centre for it”.17 This disciplined yet effortless approach cultivates “effortless wakefulness” 15, fostering the ability to “see things as they really are”.3 The physical discipline of posture and breath control directly supports this mental aim of non-attachment and presence, establishing a direct causal link between the physical form and the desired mental state.

Cultivating Presence: From Formal Practice to Daily Awareness

The formal seated practice of zazen is not an end in itself but serves as a foundational training. Its ultimate purpose is to “bring what you learn from it into every aspect of your life”.3 The awareness cultivated on the cushion is intended to permeate all daily activities. The overarching objective is to “develop the ability to be focused and present, responding appropriately to changing circumstances”.1

The relationship between formal zazen and its integration into daily life is a dynamic feedback loop. Zazen cultivates essential skills such as concentration, awareness, and non-attachment.1 These cultivated capacities are then applied to the challenges and opportunities of everyday existence, transforming mundane activities into opportunities for practice.1 The insights and difficulties encountered in daily life, in turn, provide valuable feedback that deepens and refines formal zazen. This continuous interplay suggests that Zen is not a compartmentalized practice but a seamless, evolving way of being. The ability to “let go” of attachments, a skill honed in zazen, is particularly crucial, as “not being able to let go is often the source of many of our difficulties, and creates ongoing suffering”.1 Thus, zazen is not merely about finding peace on the cushion, but about developing the mental flexibility and presence to navigate the inherent impermanence and changing circumstances of everyday existence with equanimity and appropriate responsiveness.

Zen in Motion: Integrating Practice into Daily Life

Zen’s holistic nature is most profoundly demonstrated in its integration of meditative principles into all aspects of daily life, transforming even the most mundane tasks into opportunities for continuous awakening.

Mindful Movement: Kinhin and Beyond

Following periods of seated meditation, practitioners engage in kinhin, or walking meditation.1 This practice is specifically designed to “bring the stillness of zazen into our everyday lives” 1, ensuring that the focused attention cultivated on the cushion is maintained even in motion. Kinhin involves walking in single file, often quite close to the person in front, with hands held in the shashu mudra (right hand holding the left thumb, left hand covering the right, at waist level).1 The core objective is to develop the ability to be focused and present, “responding appropriately to changing circumstances,” without developing “attachment to sitting and stillness, nor attachment to walking and motion”.1 This emphasizes that the internal state of awareness is paramount, transcending the external form of the activity.

Beyond formal kinhin, the principle of mindful movement extends to any physical activity. For instance, some practitioners utilize running as a means to practice being in the moment.18 The essence is to approach actions “slowly and deliberately,” dedicating one’s “mind completely on the task”.18 This approach highlights that the body is not merely a vessel but a direct avenue for cultivating mindfulness and presence. This embodies the concept of “dropping the bodymind” 7 not as an abstract idea, but as a lived experience where the physical act itself, performed with full attention, becomes the practice, making spiritual insight accessible through engaged, embodied action.

Nourishing Body and Spirit: Mindful Eating and Gratitude

Eating, a fundamental human activity, is transformed into a profound Zen practice. This involves applying the principle of issoku, which means doing “one thing at a time with purpose and integrity”.4 Mindful eating entails focusing solely on the meal, consciously avoiding distractions such as screens, chewing slowly, and deeply appreciating the nourishment provided.4 This practice not only aids metabolism and helps prevent overeating but also fosters a healthier, more intentional relationship with food.4

During mealtimes, particularly in Zen retreats, the practice is further deepened through chanted sutras. These chants encourage the development of a “spirit of gratitude for everything that has contributed to the availability of this food”.2 They also prompt practitioners to remember “those who are not so fortunate,” fostering an experience of “the interdependence between the giver and the receiver”.2 This explicitly links a seemingly mundane activity to the Mahayana ideal of collective liberation. By bringing full presence and gratitude to the act of eating, one naturally expands their awareness to the vast web of life that supports them, cultivating compassion for all beings and moving beyond simple personal development. Additionally, the Confucian principle of hara hachibunme (eating until eighty percent full) is highly valued in Zen, contributing to stable energy and sustained focus throughout the day.4

Work as Practice: Concentration, Purpose, and Ethical Conduct

The workplace, often perceived as a source of stress and distraction, is viewed in Zen as a rich environment for practice. Zen principles can be applied to “boost your career & achieve unimaginable success” 19, promoting “disciplines and self-control that contribute to mutually beneficial productivity”.19

Practical applications for the workday include:

- Creating “breathing space”: Waking up 30 minutes earlier to introduce a sense of purpose and intention to the start of the day.4

- “Micro-cleaning”: Inspired by Zen Buddhist monks who spend hours cleaning to clear their minds, this involves dedicating 10-15 minutes daily to clean a specific section of one’s home.4

- Mono-tasking (issoku): Concentrating on one task or project at a time to significantly improve productivity, acknowledging that the brain can take up to 25 minutes to regain focus after a distraction.4

- Prioritizing daunting tasks: Completing the most challenging tasks earlier in the day, aligning with the brain’s optimal function for short-term memory tasks in the morning.4

- Taking full breaks: Allowing the mind to fully rest during breaks by avoiding digital distractions and instead engaging in light stretching and breathing exercises.4

Samu, or voluntary activity, is a fundamental Zen practice, explicitly referred to as “meditation in action”.2 It involves performing daily tasks such as cleaning, cooking, or administrative work with a “spirit of giving and concentration,” directly applying the focus learned in zazen to secular activities.2

Beyond productivity, Zen emphasizes ethical conduct as the “building block of the house” for effective meditation practice and a peaceful, healthier life.21 This involves adhering to “five core commitments”: refraining from harmful actions such as lying, stealing, killing (or harming), inappropriate use of intoxicants, and sexual misconduct. It also entails actively engaging in virtuous actions, including being available to help others.21 The principles of ethical conduct are meant to be present “on and off [the] meditation cushion,” influencing daily choices and behavior.21 The discipline cultivated through ethical living “provides us with the support to slow down enough and to be present enough so that we can live our lives without making a mess”.21

The application of Zen principles to work transforms professional life beyond mere economic activity. It elevates work into a primary arena for spiritual growth, where challenges like denied promotions or unwanted assignments become opportunities for cultivating “intuitive insight” and a “lucid, insightful, and powerful way of self-development and expression”.19 This deep integration with ethical conduct means that genuine Zen practice cultivates character and integrity, not just mental states, fostering “mutually beneficial productivity” 19 and a more harmonious work environment.

Community and Connection: The Sangha as a Mirror

Zen, while deeply personal, strongly emphasizes “collective practice: being together” within a community, or sangha.2 This communal aspect is considered vital for spiritual development. Practitioners “evolve together, taming their fears, doubts and desires,” with others serving as a “precious mirror of their progress on the Buddha’s Path”.2 This mutual reflection provides invaluable feedback and support that is often difficult to gain in isolation.

Practicing in a group, such as a dojo or temple, is explicitly preferred over solitary practice, as the “presence of other practitioners generates a powerful collective energy and allows you to benefit from authentic teaching”.2 The analogy of a fire with multiple logs illustrates how collective practice sustains warmth and energy more effectively than a single log.2 Joining a sangha and establishing a relationship with a spiritual master are considered crucial steps for advancing along the Way of Zen, providing essential guidance and support.2 This guidance and communal support are particularly critical for navigating intense practices like Daijo Zen, which can present significant challenges and potential pitfalls if undertaken without a “very clear, strict container”.24 The sangha and teacher provide the necessary structure to ensure correct direction and prevent negative outcomes.

The Five Styles of Zen: A Spectrum of Intent and Realization

The “Five Styles of Zen,” as classified by Kuei-feng Tsung-mi and later elucidated by Yasutani Roshi, offer a nuanced lens through which to understand the diverse motivations and depths of Zen practice. While they can be seen as a progression, they also represent distinct approaches to the path, each with its own purpose and philosophical underpinnings.

Table 1: The Five Styles of Zen: A Comparative Overview

| Zen Style | Translation/Meaning | Core Motivation/Purpose | Key Characteristics/Focus | Relationship to Buddhist Goals | Examples/Manifestations |

| Bompu Zen | “Ordinary Zen” / “Usual Zen” | General well-being, stress reduction, improved concentration, physical health, character building. | Accessible to anyone; no specific philosophical or religious goals. | No specific philosophical/religious goals; therapeutic. | Modern Western meditation, apps, martial arts, Taoist longevity practices, Zen Arts (if ends in themselves). |

| Gedo Zen | “Outside Way Zen” | Worldly achievements, extraordinary powers, physical feats, material goals, altered states of consciousness, rebirth in heavens. | Often associated with non-Buddhist systems (Hindu Yoga, Confucian practices); focus on self-mastery for external outcomes. | Not considered Buddhist Zen; aims diverge from Buddhist enlightenment. | Walking on sword blades, paralyzing sparrows, achieving specific powers. |

| Shojo Zen | “Hinayana Practice” / “Small Vehicle Zen” | Personal liberation from suffering; individual enlightenment. | Focus primarily on self; explores world through direct experience; believes in dual reality (self separate from whole). | Buddhist, but not Buddha’s highest teaching; limited to individual peace. | Examining causes of personal difficulty/confusion; striving for psychological calm. |

| Daijo Zen | “Great Practice Zen” / “Mahayana Zen” | Seeing one’s true nature (kensho); realizing interconnectedness of all beings; liberation of all beings. | Motivation expands beyond personal liberation; effortful way; uses koan study and intense concentration. | True Buddhist Zen; aims for universal salvation; can be “poisonous” if misused. | Koan practice (e.g., “what is Buddha nature?”); watching/counting breath for concentration. |

| Saijojo Zen | “Highest Vehicle Zen” / “Easy and Perfect Zen” / “Great and Perfect Practice” | Practitioner understands they are already inherently awakened; perfect expression of awakened nature. | No “trying to realize” or “goal”; synonymous with shikantaza (“just sitting”); “dropping the bodymind.” | Highest Buddhist Zen; effortless embodiment of true nature. | “Practicing practice”; simply sitting and being; daily life as meditation. |

Historical Context: Kuei-feng Tsung-mi

Kuei-feng Tsung-mi (780-841) was a highly influential Tang dynasty C’han master and the fifth Ancestor of the Hua Yen tradition in China.6 His intellectual contributions extended to efforts to integrate Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, and he was renowned for systematically classifying Buddhist doctrines.8 Tsung-mi’s classification of Zen into these five styles was part of a broader, sophisticated attempt to reconcile various approaches to practice and provide a comprehensive understanding of the spiritual landscape.8 This systematic approach was not merely an academic exercise but a deliberate effort to map the diverse motivations and depths of Zen, guiding practitioners towards what he considered the most profound and ethically sound path, while also addressing potential misinterpretations or “one-sided” practices within the tradition itself.

Bompu Zen: Cultivating Universal Well-being

Definition and Core Motivation: Bompu Zen, often translated as “Ordinary Zen” or “Usual Zen,” represents the most accessible form of Zen practice.3 It is entirely free from specific philosophical or religious content.3 Its primary motivation is to enhance general well-being, reduce stress, improve concentration, and promote physical health.3 It is also believed to cultivate personality and strengthen character, enabling individuals to face life’s difficulties with greater ease.3

Accessibility and Broad Appeal: Given its non-religious nature, Bompu Zen holds broad appeal and is accessible to anyone, regardless of their existing beliefs or lack thereof.13 It is frequently encountered in modern Western meditation practices, including popular meditation applications, martial arts classes, and corporate wellness programs.7 Fundamentally, it serves “therapeutic” purposes, often likened to an “aspirin” or “pain reliever” for mental and physical discomfort.7

Everyday Manifestations and Benefits: Through the practice of Bompu Zen, individuals learn to “concentrate and control their minds” 13, a foundational mental discipline often overlooked in conventional education. This mental training assists in retaining learned information, resisting temptations, and severing attachments.13 The practice allows the body and mind to “function freely,” fostering calmness and the capacity to “face whatever is arising for us without panicking”.7

Limitations: Despite its undeniable benefits, Bompu Zen is considered limited in its scope from a deeper Zen perspective. It “cannot resolve the fundamental problem of man and his relation to the universe” because it fails to “pierce the ordinary man’s basic delusion of himself as distinctly other than the universe”.13 While it provides temporary relief from mental contraction and duality, it does not lead to the ultimate liberation (satori) that is the aim of higher Zen forms.7 This suggests that while Bompu Zen is a valuable starting point, a practitioner seeking deeper spiritual insight must eventually recognize and transcend its limited scope.

Gedo Zen: The Pursuit of Worldly Mastery

Definition and Distinctions: Gedo Zen, or “Outside Way Zen,” refers to Zen-like practices undertaken for worldly achievements, often associated with non-Buddhist systems such as Hindu Yoga or Confucian practices.3 It signifies practices that exist “outside of our life” or “outside the normal experience of everyday life”.3

Motivations: The primary motivations for Gedo Zen revolve around achieving “worldly achievements” [User Query]. This includes developing “extraordinary powers” (siddhis), performing “certain physical feats,” or attaining “specific material goals”.3 Examples cited involve impressive feats such as “walking barefooted on sharp sword blades or staring at sparrows so that they become paralyzed”.13 Another motivation is to achieve “rebirth in various heavens”.13 These achievements are often attributed to the cultivation of joriki, a strength or power gained through strenuous mind concentration.13

Critiques and Divergence from Buddhist Zen Goals: From a traditional Buddhist perspective, Gedo Zen is explicitly “not considered a Buddhist meditation”.15 A Zen practice that “aims solely at the cultivation of joriki for such ends is not a Buddhist Zen”.13 It is described as an “intoxication,” akin to alcohol or drugs, that temporarily transports one out of their direct experience by imposing external cosmologies (e.g., attributing experiences to “grace of God,” “Shiva,” or “Jesus”).7 Zen Buddhists do not seek rebirth in heavens, as these realms are considered “altogether too pleasant and comfortable,” potentially leading one away from the rigorous practice of zazen.13 Furthermore, it is believed that merit in heaven can eventually expire, leading to a fall into less favorable realms.13 The pursuit of external powers or a comfortable afterlife fundamentally diverges from the ultimate Buddhist Zen goal of enlightenment (satori) and the realization of one’s essential nature, which is about liberation from the illusions of the world rather than power over it.13

The focus on cultivating “supranormal powers” and “worldly achievements” in Gedo Zen highlights a critical divergence from the core aims of Buddhist Zen. While the development of powerful concentration (joriki) is a byproduct, its application for external gain is seen as a misdirection. This implies that seeking external power without internal liberation can lead to further delusion or attachment, rather than genuine freedom. This distinction underscores that true Zen prioritizes transformative insight into the nature of reality over the acquisition of phenomenal abilities or temporary states.

Shojo Zen: The Path of Individual Liberation

Definition and Focus: Shojo Zen, or “Hinayana Practice” (“Small Vehicle Zen”), is a Buddhist practice primarily focused on “one’s own personal liberation from suffering”.3 It is termed “small vehicle” because its scope is primarily on “individual enlightenment, sometimes seen as separate from the liberation of all beings”.3

Exploring Illusion and Direct Experience: This style of meditation aims to help practitioners “examine the cause of any difficulty in your life or confusion”.3 It is an “exploration of the world around you through direct experience,” moving from illusion to enlightenment.3 It involves a “vital investigation into perception, cognition, and the nature of the world and self”.7

The “Small Vehicle” and Its Limitations: Shojo Zen is characterized by a belief in a “dual nature of reality,” where the practitioner may “see themselves as separate from the whole”.3 This approach often involves “trying to grasp at realization, presuming it’s separate from oneself,” which can lead to efforts to “make something happen” in practice rather than simply attending to present experience.7 Practitioners may strive to achieve a “clear state of mind” or mushin-jo (a state free of confusion), believing this to be an inherently “better or ultimate state of mind”.3 This is considered a “conditional freedom” 7 because its root lies in how “self-image operates, thinking freedom is something to ‘have’ rather than realizing it’s ‘who and what we are'”.7 While it is a Buddhist practice, it “differs from Buddha’s highest teaching” 3 and is considered “somewhat more wakeful” than Bompu or Gedo Zen, yet still limited in its scope.7

The designation of Shojo Zen as the “small vehicle” highlights a key philosophical distinction: while individual liberation is a valid and necessary initial goal, it is considered incomplete if it does not expand to recognize the profound interconnectedness of all beings. The critique that it can be “based on trying to grasp at realization, presuming it’s separate from oneself” points to a subtle trap: the very act of striving for individual enlightenment can inadvertently reinforce the illusion of a separate self that needs to be enlightened, rather than realizing inherent awakening. This implies a progression of understanding within the Buddhist path, where a practitioner must eventually move beyond the limitations of Shojo Zen to realize the full scope of the Dharma.

Daijo Zen: Embracing Universal Interconnectedness

Definition and Core Buddhist Goal: Daijo Zen, or “Great Practice Zen” (also known as “Mahayana Zen” or “Great Vehicle Zen”), is considered “truly Buddhist Zen”.3 Its explicit Buddhist goal is “seeing one’s true nature (kensho) and realizing the interconnectedness of all beings”.3 This practice aims to break free from the illusions of the world to experience an absolute, undifferentiated reality.3

Motivation: Beyond Personal Salvation to Collective Awakening: The motivation for Daijo Zen “expands beyond personal liberation to include the enlightenment of all beings”.3 This profound aspiration is embodied in the “Four Great Vows” of the Bodhisattva, which begin with “All beings without number, I vow to liberate”.7 Through this practice, individuals come to understand “how their state affects everyone else, and vice versa,” fostering “deeper intimacy and compassion” for all beings.3 The essential motivation, often given lip service but implicitly crucial, is “in order to save all beings”.24

Associated Practices: Koan Study and Intense Concentration: Daijo Zen is often described as an “effortful way” and is primarily associated with Japanese Rinzai lineages.7 Common practices include “watching or counting the breath” to develop powerful concentration, and “koan practice”.10 Koans are paradoxical “teaching questions that require something beyond concept for its resolution,” pointing directly to essential nature (e.g., “what is life, what is Buddha nature, what is my original mind, what am I?”).17 The “intensity of questioning then breaks thought what mere thought cannot”.24

Potential Pitfalls: The “Poisonous Aspect” and the Need for Guidance: Daijo Zen is described as “flirt[ing] so much with dualism (or embraces it full-on),” making it “akin to taking controlled amounts of poison as medicine”.24 This “poisonous aspect” arises because the intense “pushing” to attain a goal can inadvertently “solidify the notion of yourself as incomplete”.24 The powerful concentration developed, if misused without correct motivation, can lead to suppressing parts of oneself, forcing specific mental states, or even “damage the compassion and the ability to relate well with others”.24 This can result in practitioners becoming “one-sided, attached to emptiness, and lacking compassion and ability to relate to or even help others very much”.24 Therefore, this demanding training “requires a very clear, strict container” including a qualified teacher, a supportive community, a structured training form, and a dedicated practice place.24

The description of Daijo Zen as an “effortful way” with a “poisonous aspect” reveals a profound paradox: intense striving is employed to reach a state that is ultimately effortless. This highlights that while powerful practice can break through delusion, it can also reinforce dualism and egoic attachment if not properly guided. The repeated emphasis on the necessity of a “teacher, community, training form, and practice place” establishes a critical causal link: without this strict container, the intensity of Daijo Zen can lead to misinterpretations, attachments, and “skewed” development, potentially damaging the very compassion and interconnectedness it aims to cultivate.

Saijojo Zen: The Effortless Expression of Awakened Nature

Definition: Saijojo Zen, often called “Highest Vehicle Zen” or “Easy and Perfect Zen” (“Great and Perfect Practice”), represents the most advanced and profound form of Zen.3 In this stage, the practitioner “understands that they are already inherently awakened and integrated with their true nature” [User Query]. There is “no longer a ‘trying to realize’ or a ‘goal’ to achieve, but rather a perfect expression of one’s awakened nature in every moment”.3

Synonymous with Shikantaza: Just Sitting, Just Being: Saijojo Zen is synonymous with shikantaza, meaning “just sitting”.7 This practice involves “observing reality and discovery of inner awareness without object of concentration”.10 It is about allowing “whatever arises to simply be, while continuing to sit”.25 Thoughts are permitted to “come and go” without any attempt to stop them or achieve a state of “nothingness”.25

Realization Beyond Striving: Inherently Awakened Nature: In Saijojo Zen, the practitioner realizes that their own looking is Buddha, without needing to seek Buddha externally.7 Dogen Zenji famously described shikantaza as “dropping the bodymind,” which means “experiencing each experience as it is, penetrating one’s True Nature, and realizing the absence of body, mind, time, or space”.7 It is characterized as a “wordless release of all gestures of grasping,” akin to opening a fist or eyes, and is understood as the “activity of primordial Awareness”.7 In this state, nothing that arises can cause confusion, separation, or identification.7 This is the actualization of one’s undefiled True-nature (bussho).17

Daily Life Manifestations of Effortless Presence: The profound sense of presence cultivated in Saijojo Zen is designed to be “applied beyond seated meditation to all aspects of daily life”.25 When thoughts inevitably arise, the practitioner gently returns “to the facts before you or to the task at hand”.25 As this practice deepens, “your entire daily life can become a form of meditation”.25 It is quite literally about “practising the practice” 3, embodying the perfect expression of one’s true nature in every moment.7

Soto Zen Root: In the Japanese Sōtō Zen school, shikantaza is considered “the root of all practice”.7 Some initial realization of shikantaza is deemed necessary to truly begin practicing Soto Zen, implying a foundational sense of being Buddha, even if initially on a feeling or intellectual level.7 The Rinzai school, however, often takes the stance that one cannot properly engage in shikantaza until they have experienced kensho.28

Saijojo Zen’s description as the “highest vehicle” where one is “already inherently awakened” and its synonymity with shikantaza signifies a profound philosophical shift. It is not about achieving something external, but about embodying one’s true nature in every moment. This implies that the distinction between the path and the goal dissolves, and “practicing practice” becomes the effortless expression of awakened being. The daily life manifestation is not about applying principles to activities, but about the activities themselves being the awakened nature, where the separation between formal practice and everyday life ceases to exist. This suggests a causal relationship where deep realization naturally transforms one’s entire way of being, making the “struggle for satori” obsolete.

The Interplay of Styles: Progression, Entry Points, and Nuance

The five styles of Zen, while offering a structured framework, do not necessarily represent a rigid, linear progression. Their relationship is more nuanced, encompassing different entry points, distinct approaches, and a dynamic interplay of understanding and realization.

Are They Linear? Understanding the Journey

The styles are often presented as “progress[ing] in difficulty and commitment level” 15, suggesting a hierarchical path from the accessible Bompu Zen to the profound Saijojo Zen. However, this linearity is not absolute. Gedo Zen, for instance, is explicitly “not considered a Buddhist meditation” 15, indicating it is a distinct, divergent approach outside the core Buddhist tradition, rather than a stage within it. This suggests that the “progression” is more accurately understood as a deepening of “understanding and realization” rather than merely a fixed sequence of techniques.15

Different Zen schools, such as Rinzai and Soto, emphasize distinct paths to awakening. Rinzai often focuses on kensho (“seeing one’s true nature”) through koan practice, sometimes described as “instant enlightenment” followed by gradual cultivation for integration.10 Soto Zen, conversely, places a strong emphasis on shikantaza (“just sitting”) and is often associated with a more gradual path of deepening presence.27 Despite these differences in emphasis, both schools ultimately stem from “sudden enlightenment” traditions.27 This nuanced understanding of progression, where insight can arise abruptly but requires ongoing cultivation, suggests that the “best” path is highly individualized, shaped by one’s disposition and guided by a qualified teacher and community. The framework of the five styles serves as a conceptual map for understanding different motivations and depths of realization, rather than a rigid, universal ladder.

The Role of a Teacher and Community in Guiding Practice

The role of a spiritual master and the community (sangha) is paramount in Zen practice. A spiritual master, having “travelled the path for many years or even decades,” is uniquely “able to guide the practitioner”.2 This guidance is crucial for navigating difficult moments, resolving doubts, and addressing deep questioning that inevitably arise on the path.2

Practicing in a group or sangha is explicitly preferred over solitary practice, as the “presence of other practitioners generates a powerful collective energy and allows you to benefit from authentic teaching”.2 The analogy of a fire with multiple logs highlights how collective practice sustains warmth and energy more effectively than a single log, providing a supportive environment for sustained effort.2 This guidance and communal support are particularly critical for intense practices like Daijo Zen, which, as discussed, carries a “poisonous aspect” if misused. Such practices require a “very clear, strict container” to ensure correct direction and prevent potential negative outcomes.24 The sangha and teacher provide the necessary structure and experienced oversight to navigate the profound and potentially destabilizing experiences that can arise in deeper Zen, ensuring a balanced and compassionate development.

Avoiding Misconceptions and One-Sidedness

A significant challenge in Zen practice, particularly as it spreads globally, is the potential for misconceptions and one-sided development. Yasutani Roshi, despite his immense influence in transmitting Zen to the West, was criticized for “one-sided” teachings, specifically for overemphasizing kensho (seeing one’s true nature) to the exclusion of other crucial aspects of practice.12 This highlights the inherent danger of imbalance in spiritual training.

A prominent pitfall, particularly in the intense practice of Daijo Zen, is the risk of becoming “one-sided, attached to emptiness, and lacking compassion and ability to relate to or even help others very much”.24 This illustrates that an intellectual understanding of emptiness, a core Buddhist concept, without its corresponding embodiment in compassion and ethical action, can lead to a “skewed human”.24 This emphasizes a critical observation: true Zen requires a balanced integration of wisdom (the realization of emptiness and true nature) with compassion (acting for the benefit of all beings). Without this balance, even profound insights can lead to detachment, isolation, and a lack of genuine connection, resulting in an incomplete or even harmful realization, rather than the full, integrated awakening that Zen aims for. This underscores the peril of intellectualizing spiritual concepts without their full, embodied manifestation.

Zen for Modern Life: Practical Wisdom for Contemporary Challenges

Zen is not an ancient philosophy confined to monasteries; it offers profound, practical wisdom applicable to the complexities of modern daily life, transforming challenges into opportunities for growth.

Applying Zen to Work: Productivity, Focus, and Stress Reduction

Zen principles offer a “simple and effective guide to applying ZEN Principles to Boost Your Career & Achieve Unimaginable Success”.19 This involves cultivating “disciplines and self-control that contribute to mutually beneficial productivity”.19 Practical applications for integrating Zen into the workday include:

- Creating “breathing space”: Beginning the day by waking up 30 minutes earlier allows for a more intentional and purposeful start.4

- “Micro-cleaning”: Inspired by Zen monks who clean to clear their minds, dedicating 10-15 minutes daily to clean a specific section of one’s home can purify the mind and space.4

- Mono-tasking (issoku): Concentrating on one task at a time significantly improves productivity, acknowledging that the brain takes time to regain focus after distractions.4

- Prioritizing daunting tasks: Completing the most challenging tasks early in the day aligns with optimal brain function for short-term memory.4

- Taking full breaks: Allowing the mind to fully rest during breaks by avoiding digital distractions and engaging in light stretching and breathing exercises.4

- Mindful eating at lunch: Embracing hara hachibunme (eating until 80% full), a Confucian principle valued in Zen, helps maintain focus and stable energy throughout the afternoon.4

Zen also provides a framework for navigating professional challenges, such as denied promotions or unwanted assignments, by cultivating “intuitive insight” and a “lucid, insightful, and powerful way of self-development and expression”.19 The application of Zen principles to work extends beyond superficial stress reduction; it offers a holistic framework for sustainable professional excellence, fostering deep focus, disciplined action, and resilience. This approach transforms obstacles into opportunities for growth and self-mastery, aligning with the spirit of Bompu Zen for well-being and character building.

Zen in Relationships: Presence, Compassion, and Authentic Connection

Zen fosters the capacity to “show up intimately and honestly, with one’s whole self, for and with each other, over time” in relationships.29 “True presence” is considered the “best thing we can offer another person”.29 Mindfulness plays a crucial role in enhancing relational dynamics by:

- Slowing down thoughts: This allows individuals to pay attention to their own emotions and their partner’s, preventing the avoidance of difficult conversations.30

- Clearing the mind: This facilitates a “greater connection to your partner, others, and humanity” during intimate moments.30

- Increasing bodily awareness: This enhances awareness of physical sensations and helps reduce anxiety during intimacy.30

Practical applications in relationships include: slowing down physical touch, touching purposefully, openly communicating feelings evoked by touch, and looking directly into each other’s eyes.30 These practices cultivate “genuine connection, deep emotions, and overwhelming appreciation”.30

Compassion (karuna) in Zen is not merely a feeling of sympathy but a “deep, intrinsic understanding that we are all interconnected, part of the same whole”.31 This profound understanding naturally leads to a “desire to alleviate not just our own suffering, but the suffering of others as well”.31 The emphasis on compassion in relationships is a direct and practical manifestation of the Daijo Zen principle of interconnectedness. As one’s Zen practice deepens the realization of interdependence, compassion naturally arises as a lived experience, leading to more authentic, empathetic, and fulfilling relationships. The practical advice for mindful interaction provides concrete methods for embodying this philosophical insight in daily interactions.

Facing Personal Challenges: Self-Discipline, Discomfort, and Resilience

Zen principles provide a robust framework for building self-discipline, confronting discomfort, and cultivating resilience in the face of personal challenges.32 Practical approaches include:

- Small, consistent actions: Committing to a self-discipline task for “five minutes, every day” helps build the “self-discipline muscle”.32

- Understanding “Why”: Connecting the task to a deeper motivation, such as improving health or pursuing a dream, provides sustained drive.32

- Facing discomfort: Practitioners are encouraged to “feel the pain” caused by procrastination as a motivator for change.32 Challenging oneself to “do hard things” fosters adaptability to discomfort and promotes growth through failure.33

- Making it easy to start: Reducing the initial barrier by making the first step “really easy” (e.g., simply getting on the meditation cushion) can overcome resistance.32

- Perseverance through setbacks: Viewing mistakes or missed days as “a bump in the road” rather than a reason to quit encourages learning from errors and getting back on track.32

This approach helps to “prove that difficulty, discomfort, uncertainty, resistance and fear are nothing to fear” 33, fostering “resilience, grit, determination, commitment”.33 Zen’s application to personal challenges extends beyond mere mental calm; it cultivates robust psychological fortitude. The emphasis on “facing discomfort” and “not running from things because they are hard or scary” directly applies Zen’s principle of non-attachment to aversion and the acceptance of “what is.” By consistently engaging with small discomforts and challenges, practitioners build self-discipline and develop resilience, transforming perceived obstacles into opportunities for profound personal growth. This balanced approach combines effort with self-compassion, leading to a more integrated and adaptable self.

Cultivating an Ethical Mindset Beyond the Cushion

Ethical conduct is not a separate moral code in Zen but is considered its fundamental “building block”.21 It is deemed essential for “effective meditation practice” and for living a “peaceful and happier life”.21 This involves adherence to “five core commitments”: refraining from harmful actions such as lying, stealing, killing (or harming), inappropriate use of intoxicants, and sexual misconduct. It also entails actively engaging in virtuous actions, including being available to help others.21

The “principles of Ethical Conduct are always on the back of my mind on and off my meditation cushion,” influencing daily choices and behavior.21 This integration ensures that inner transformation is reflected in outward conduct. The discipline cultivated through ethical living “provides us with the support to slow down enough and to be present enough so that we can live our lives without making a mess”.21 The strong emphasis on ethical conduct is an integral and foundational component of Zen practice. Without an ethical foundation, deeper meditative states can be unstable, or insights can be misused, potentially leading to negative outcomes like those seen in misapplied Daijo Zen (e.g., lack of compassion). The discipline cultivated through ethical living directly supports presence and prevents “making a mess” of one’s life, reinforcing Zen’s holistic nature where inner transformation must be reflected in outward conduct.

The Unfolding Path of Zen

Zen practice, far from being confined to the meditation cushion, is a comprehensive and dynamic path that permeates every facet of daily life. This report has explored how Zen principles extend into mindful movement, eating, work, relationships, and personal challenges, transforming mundane activities into opportunities for profound awakening.

Recap of Zen’s Holistic Nature

The “Five Styles of Zen” – Bompu, Gedo, Shojo, Daijo, and Saijojo – provide an invaluable and nuanced framework for understanding the diverse motivations, depths, and philosophical underpinnings of Zen practice. From the accessible pursuit of secular well-being in Bompu Zen to the effortless expression of inherent awakened nature in Saijojo Zen, these styles illuminate a spectrum of intent and realization. While Gedo Zen diverges from traditional Buddhist aims by focusing on worldly powers, Shojo Zen offers individual liberation, and Daijo Zen expands to universal interconnectedness, each style offers a unique lens through which to engage with the Zen path. The journey through these styles is not necessarily linear but rather a deepening of understanding and realization, often requiring the crucial guidance of a teacher and the supportive container of the sangha to navigate its complexities and avoid pitfalls like one-sidedness or attachment to emptiness without compassion.

The Continuous Journey of Awakening in Every Moment

Ultimately, Zen is not about achieving a static, distant goal, but about the continuous “actualization” or “perfect expression of one’s awakened nature in every moment”.1 It is a path of “intimacy, awakening, and ultimately full enlightenment,” unfolding in the midst of everyday life.6 This demanding yet profoundly rewarding journey cultivates essential qualities such as patience, endurance, discipline, curiosity, and a deep thirst for understanding existence.1 Zen teaches that the profound is found in the ordinary, and true liberation is realized not by escaping the world, but by fully engaging with it, moment by moment, with unwavering presence, profound wisdom, and boundless compassion.

Works cited

- How To Practice Zen – Zen Studies Society, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://zenstudies.org/teachings/how-to-practice/

- Zen and everyday life | Association Zen Internationale, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.zen-azi.org/en/zen-vie-quotidienne

- Zazen Meditation: Benefits, Types, and More – Healthline, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/zazen

- 12 Zen Buddhist Practices That Will Change Your Life — The …, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.thedenizenco.com/journal/zen-buddhist-practices

- Zen Buddhism by D. T. Suzuki | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/literature-and-writing/zen-buddhism-d-t-suzuki

- What’s On the Path? Part Twelve: Householder Practice, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.rzc.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Bodhisattva-12-Householder-Practice-8-18-24.pdf

- Begin Here: Five Styles of Zen | White Wind Zen Community, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://wwzc.org/dharma-text/begin-here-five-styles-zen

- Zongmi – New World Encyclopedia, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Zongmi

- Guifeng Zongmi – Wikipedia, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guifeng_Zongmi

- Zazen – Wikipedia, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zazen

- Yasutani Roshi: The Hardest Koan – Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://tricycle.org/magazine/yasutani-roshi-hardest-koan/

- 安谷 (白雲) 量衡 Yasutani (Hakuun) Ryōkō (1885-1973) – Terebess.hu, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://terebess.hu/zen/mesterek/yasutani.html

- ZEN 4: The Five Varieties of Zen | Vinaire’s Blog, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://vinaire.me/2018/10/18/zen-4-the-five-varieties-of-zen/

- Zen Meditation: An Introduction and How to Practice at Home – Retreat Guru, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://blog.retreat.guru/zen-meditation

- A Primer on Zen Meditation – Psych Central, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://psychcentral.com/health/zen-meditation

- Introductory Lectures on Zen Training – The Matheson Trust, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.themathesontrust.org/papers/fareasternreligions/Introductory%20Lectures%20on%20Zen%20Training.pdf

- Zazen meditation (Zen) | Encyclopedia of World Problems and …, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://encyclopedia.uia.org/human-development/zazen-meditation-zen

- 12 Essential Rules to Live More Like a Zen Monk, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://zenhabits.net/12-essential-rules-to-live-more-like-a-zen-monk/

- The Zen of Work: A Simple and Effective Guide to Applying ZEN Principles to Boost Your Career & Achieve Unimaginable Success | Book 1 | For both White Collar & Blue Collar in the Workplace eBook : CH SIU, ALYSSA – Amazon.com, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Zen-Work-Effective-Principles-Unimaginable-ebook/dp/B0CVNQQM7F

- The Zen of Work: A Simple and Effective Guide to Applying ZEN Principles to Boost Your Career & Achieve Unimaginable Success | Book 1 | For both White Collar & Blue Collar in the Workplace: 9798879608083 – Amazon.com, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Zen-Work-Effective-Principles-Unimaginable/dp/B0CVQ7L7VL

- Beyond Sitting Still: Put Your Ethics into Action for a More Peaceful Life – Shilpa Kapilavai, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://shilpakapilavai.com/beyond-sitting-still-put-your-ethics-into-action-for-a-more-peaceful-life/

- Ethical Principles – San Francisco Zen Center, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.sfzc.org/about-sfzc/how-sfzc-operates/ethical-principles

- Ethical Principles and Procedures | New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.zencare.org/ethical-principles-and-procedures

- What are the practices associated with Daijo Zen? : r/Meditation, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Meditation/comments/81615k/what_are_the_practices_associated_with_daijo_zen/

- Just Sitting: Practicing Shikantaza in Everyday Life – Huayruro, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.wearehuayruro.com/post/just-sitting-practicing-shikantaza-in-everyday-life

- What style of Zen do you prefer? – Reddit, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/zen/comments/1toh1n/what_style_of_zen_do_you_prefer/

- Philosophical differences between Soto and Rinzai? – Dharma Wheel, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.dharmawheel.net/viewtopic.php?t=35406

- Lesson-4-Rinzai-and-Soto-Zen.pdf, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.clearwayzen.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Lesson-4-Rinzai-and-Soto-Zen.pdf

- Relationship: More On Zen by Norman Fischer – Stillness Speaks, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.stillnessspeaks.com/relationship-more-zen-fischer-shambhala-3-3/

- Zen and the Art of Making Love | Psychology Today South Africa, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.psychologytoday.com/za/blog/sexual-mindfulness/202102/zen-and-the-art-of-making-love

- Unfolding the Lotus: A Compassionate Response to Life’s Challenges – Steven Webb, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://stevenwebb.com/unfolding-the-lotus-a-compassionate-response-to-lifes-challenges/

- The Building Self-Discipline Challenge – Zen Habits Website, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://zenhabits.net/discipline-challenge/

- The Challenge of Doing Hard Challenges – Zen Habits Website, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://zenhabits.net/hard-challenges/